About Fishwise

FishWise, founded in 2002, is a nonprofit marine conservation organization based in Santa Cruz, California. FishWise promotes the health and recovery of ocean ecosystems by providing innovative market-‐based tools to the seafood industry. The organization supports seafood sustainability through environmentally responsible business practices. FishWise is a founding member of the Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions, with staff serving on the Environmental Stakeholder Committee of the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation (ISSF), the Fisheries Advisory Council of Fair Trade USA, and participates in a variety of other industry and marine conservation initiatives. FishWise works with companies throughout the supply chain and is currently partnered with several of North America’s largest retailers, including Safeway Inc., Target Corp., and Hy-‐Vee Inc. Through its relationships with retailers and suppliers, FishWise works with over 65 million pounds of seafood per year and more than 100 species from farmed and wild sources. Its retail partners maintain more than 3,700 storefronts in North America.

About this document

This white paper on human rights in the seafood industry follows FishWise’s white paper on seafood traceability. It is hoped that this document will create connections across businesses, organizations, and governments to spark conversation and action as to how the seafood industry can work together to eliminate human rights abuses and illegal products from supply chains. If all stakeholders work together to elevate these issues of human dignity, and incorporate them into business practices, human rights within the seafood industry can be improved significantly.

©2013 FishWise. All rights reserved. Sections of this report may be copied with permission of FishWise. Please acknowledge source on all reproduced materials.

Definitions

Labor Rights

In this paper, labor rights refer to a broader category of issues than trafficking or modern slavery. The International Labour Organization’s (ILO) ‘Declaration of the Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work’ places these rights into core standards: freedom of association, right to collective bargaining, prohibition of forced labor, elimination of the worst forms of child labor, and non-‐discrimination in employment (ILO 1998).

Forced labor

Forced labor is any working condition under which an individual is threatened or coerced to act against his or her will. Threatening or coercive working conditions nullify any prior consent-‐to-‐work agreements or contracts between victim(s) and employer(s) (USDOS 2013).

Human trafficking

According to the 2013 U.S. State Department’s 2013 Trafficking in Person’s Report (hereafter, TIP report), ‘Human trafficking’ and ‘trafficking in persons’ are umbrella terms for “the act of recruiting, harboring, transporting, providing or obtaining a person for compelled labor or commercial sex through the use of force, fraud, or coercion” (USDOS 2013). Trafficking victims can include both individuals smuggled across borders and those born into state servitude (USDOS 2013). At the core of this issue is the traffickers’ intention to exploit or enslave another human being, and the coercive, underhanded practices they engage in to do so (USDOS 2013).

The international definition set forth by the United Nations (UN) Office on Drugs and Crime (ODC) defines Trafficking in Persons as “the recruitment, transportation, transfer, harbouring or receipt of persons, by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation” (UNODC 2013).

Smuggling of migrants

The United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime defines ‘smuggling of migrants’ as “the procurement, in order to obtain, directly or indirectly, a financial or other material benefit, of the illegal entry of a person into a State Party of which the person is not a national or a permanent resident” (UN 2001).

Modern Slavery

This is a general term often used when referring to holding a person in compelled service, including trafficking, forced labor, involuntary servitude, and bonded labor (US DOS 2013b).

Human and Labor Rights Abuses in Seafood Supply Chains

Background

It is estimated that the livelihoods of 10-‐12% of the world’s population (660-‐820 million people) are directly or indirectly dependent upon marine capture fisheries and aquaculture, which produce over 90 million tons of fish every year (FAO 2012). While the majority of the seafood industry operates legally and employs fair labor practices (FAO 2012; ILO 2013), a number of publications have recognized and documented the pervasiveness of human trafficking, forced labor, child labor, and egregious health and safety violations in marine capture, aquaculture, and seafood processing operations (Pearson et al. 2006; Skinner 2008; Brennan 2009; UNIAP 2009; EJF 2010; Robertson 2011; Stringer et al. 2011; Motlagh 2012; PBS 2012; Sifton 2012; PBS 2012; Surtees 2012; EJF 2013; IEDE 2013; ILO 2013; ILRF/WWU 2013; Stringer and Simmons 2013; Stringer et al. 2013).

About 660-820 million people are directly or indirectly dependent upon marine capture fisheries and aquaculture.

While forced labor and human trafficking in fisheries and aquaculture is not a new phenomenon, the problem has been exacerbated in recent years by globalization of the seafood industry; illegal, unregulated, and unreported (IUU) fishing; increased competition for marine resources; and the availability and mobility of low-‐cost migrant labor (ILO 2013). Both genders are involved in the seafood industry. Victims on board fishing vessels are primarily men and boys ranging from age 15 to over 50 (UNIAP 2009; Surtees 2012). Processing facility workers are most often women and girls (Sifton 2012; IEDE 2013; ILRF/WWU 2013).

Globally, it is estimated there are over 20 million people working under coercive or forced labor conditions -‐ primarily migrant workers in labor-‐intensive industries in the informal (e.g. untaxed and undocumented sectors) and black-‐market (e.g. trade in illegal goods) economy (ILO 2013). The recruiting processes and working conditions of many fishers and seafood industry employees are so egregious that these human and labor rights abuses have been referred to as ‘modern slavery’ (EJF 2010; ILO 2013). Case studies from the last decade cite examples of fraudulent and deceptive recruiting, 18 - 20 hour workdays, homicide, sexual abuse, child labor, physical and mental abuse, abandonment, refusal of fair and promised pay.

Over 20 million people working under coercive or forced labor conditions such as 20 hour workdays, homicide, child labor.

Abuse Aboard Fishing Vessels

Some of the worst human rights and labor violations in the seafood industry occur onboard fishing vessels (ILO 2013). Violations are often committed by the senior crew and captain (ILO 2013). Case studies from the last decade cite examples of recruitment under false pretenses, 20 hour workdays, child labor, physical and mental abuse, abandonment, and withholding of pay and identifying documents (Skinner 2008; EJF 2010, 2013; ILO 2013). In one report, over half the victims interviewed reported seeing a fellow crewmember murdered (UNIAP 2009).

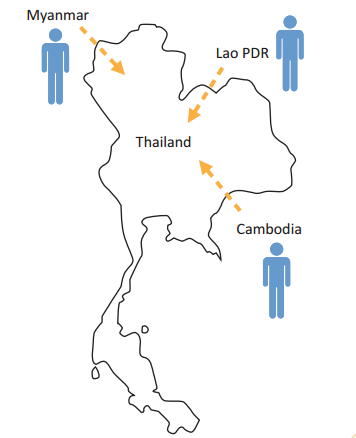

Abuse in Seafood Processing

Most case studies of labor and human rights abuses in seafood processing and packaging involve migrant workers in both licensed and non-‐licensed operations in the southern provinces of Thailand (UNIAP 2009; Sifton 2012; ILRF/WWU 2013; IEDE 2013). As previously mentioned, migrant labor is used to cut costs and to fill the void created by a lack of available Thai workers. Some of the most egregious abuses occur in the Thai shrimp industry which is highly dependent upon migrant labor, including the use of underage workers, refusal of pay, charging workers excessive fees for work permits, and an ineffective auditing regime (ILRF/WWU 2013; Westlund 2013).

Four hundred thousand Burmese migrants work in Samut Sakhon, where 40% of Thailand’s shrimp is peeled and frozen for export (Motlagh 2012). Around 200 peeling sheds are officially registered with Thailand’s Department of Fisheries. Less than 100 peeling sheds are also registered with Thai Frozen Foods Association, even though registration is required to legally supply to other members and export to international markets (EJF 2013b). Estimates for unregistered peeling sheds operating in Samut Sakhon range from 400 to 1,300, with some organizations putting the number closer to 2,000 (EJF 2013b; Motlagh 2012). These unregistered facilities are not subject to any regulation or oversight, and are where the most severe abuses occur.

Estimates for unregistered peeling sheds operating in Samut Sakhon range from 400 to 1,300, with some organizations putting the number closer to 2,000.

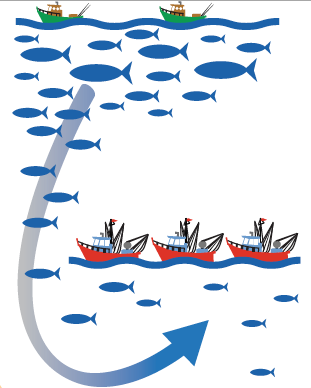

1) Overfishing has led to a global decline of marine fish stocks, increasing the competition for marine resources.

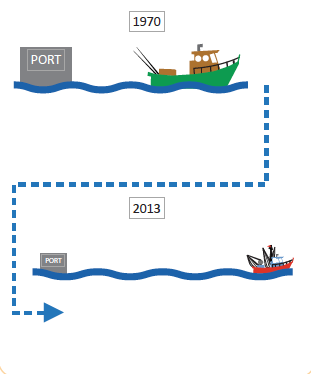

2) In order to find more plentiful fishing grounds, vessel operators are forced to travel further out to sea, or to remote regions, for longer periods of time.

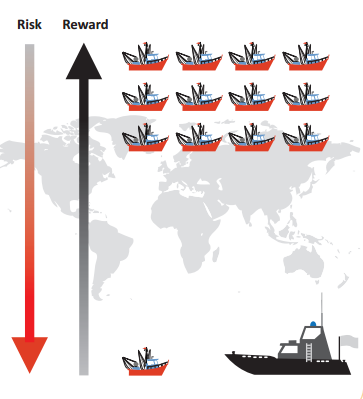

3) The global nature of the seafood industry combined with poor enforcement creates a low risk/high reward scenario, allowing for human rights abuses and illegal fishing to go undetected.

4) Vessel owners and operators are increasingly turning to migrant workers, who are often desperate for work and vulnerable to trafficking and labor abuses.

Recommendations for Supply Chains

Outlined below are recommendations to improve human and labor rights within seafood supply chains (Figure 3). These steps are based on case studies, industry guidance documents, recommendations from other sectors, and conversations with experts, and draw parallels from work on illegal fishing and sustainability improvements.

1. Create a Company Policy on Human Rights

Human and labor rights have gained attention in many sectors, such as electronics, coffee, chocolate, garment, and textiles. Consumers are increasingly aware of the global nature of modern supply chains, and the stories of associated human rights abuses. Companies that have found great success in improving their supply chain practices have been transparent about their efforts to improve, with the first step being a public policy on human rights and ethical sourcing.

Consumers are increasingly aware of the global nature of modern supply chains. Be transparent in human rights policies

2. Conduct a Risk Assessment

As with all supply chain improvement efforts, it is important to quantify risk using objective criteria, then address the areas of highest risk first. While the discussion of human rights in the seafood industry is nascent, there are some reports and guidance documents that will be helpful to those looking to make improvements. We suggest that this risk assessment be conducted at the same time as an assessment of product at risk of being illegal or mislabeled.

As with all supply chain improvement efforts, it is important to quantify risk using objective criteria, then address the areas of highest risk first.

Marine living resources crimes (such as illegal fishing) and human trafficking have been found to co-occur, so work to eliminate both of these concerns is a priority (UNODC 2011). Once these high-risk items have been identified, research into sources and supply chains can lead to further engagement with the relevant companies and countries. For example, recommendations for the Thai government for shrimp are outlined in the EJF ‘The Hidden Cost’ report (2013b). For a list of risk by country, we suggest referring to the TIP (2013) report and DOL (2012) reports. Also, Free2Work has a short video explaining how it assesses worker rights in various supply chains.

Marine living resources crimes (such as illegal fishing) and human trafficking have been found to co-occur.

3. Work to Improve Supply Chain Traceability

Without comprehensive traceability that allows companies to identify the source countries and regions of processing, human rights abuses and illegal fishing concerns cannot be identified and eliminated from supply chains. Several initiatives are underway to improve the traceability of seafood supply chains. For more information and recommendations for the industry please see the FishWise white paper on seafood traceability: Without a Trace II: An Updated Summary of Traceability Efforts in the Seafood Industry.

Without traceability, human rights abuses and illegal fishing concerns cannot be identified and eliminated from supply chains.

4. Work to Eliminate all IUU Product & Combat Illegal Fishing

Illegal fishing is often closely linked to human rights abuses. Working to eliminate all illegal product from supply chains, at a global level, will require work on many fronts to be successful. Some suggested actions to combat IUU include supporting IUU legislation at the international and national scale, creating a policy around illegal products and communicating the policy to vendors, showing support for a mandatory Unique Vessel Identifier for all large fishing vessels (such as the IMO number) and the creation of a Global Record of fishing vessels, ensuring vessels have the proper monitoring system equipment on board, not purchasing from vessels with flags of convenience, and reviewing all supply chains with transhipment to ensure they are operating legally.

Working to eliminate all illegal product from supply chains, at a global level, will require work on many fronts to be successful.

5. Seek Certification or Adhere to Best Practice Guide

This paper outlines several certifications for social compliance and human rights within the seafood supply chain. However, this paper does not attempt to compare and contrast these certifications to determine which are the most rigorous and address the greatest number of concerns. Companies should research the various certifications and choose the one best suited to their supply chain. A consultant or certification body, many of which are outlined in this paper (with contacts provided in Appendix III), can help facilitate this decision-‐making. Another example of a best practice is to ensure workers have access to a reporting mechanism such as an anonymous hotline to report abuses (e.g. Polaris Project).

Companies should research the various certifications and choose the one best suited to their supply chain.

6. Support Human Rights Legislation

In this white paper, we reviewed the status of important international human rights legislation. A summary of each, along with the countries that have already ratified legislation, is included in Appendix II. Letters of support to the national governments of seafood sources, processing, and final sale locations will help these measures be enacted. Currently, the Work in Fishing Convention (No. 188) and Cape Town Agreement require more ratifications for them to go into effect, and the STCW-‐F Convention (already in effect) would benefit from additional ratifications by nations with a strong maritime presence.

Letters of support to the national governments of seafood sources, processing, and final sale locations will help these measures be enacted.

7. Engage with Governments of Countries with Human Rights Concerns

The TIP report (2013), DOL report (2012), and other special investigations have published lists of countries with human rights concerns, with many focused on forced labor and trafficking. Similarly, the U.S. and E.U. have released IUU ‘watch lists’, and it is known that IUU and human rights abuses often occur together (UNODC 2011). Companies should identify the nations they source from that are also on these lists and send letters to the governments of countries with concerns, requesting that they improve their requirements and enforcement to ensure these conditions do not persist. Specific suggestions for the government of Thailand, in respect to shrimp farming, are provided in the EJF report “The Hidden Cost” (2013b).

Companies should send letters to the governments of countries with concerns, requesting that they improve their requirements and enforcement to ensure these conditions do not persist.

8. Conduct Transparent Self-‐Reporting

Companies and customers alike are intensifying their focus on Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). More than 50% of companies have integrated sustainability into strategic planning. Mission and values and external communication typically have the greatest integration with sustainability, while supply chain management and budgeting have the least (McKinsey & Company 2011). Concurrently, almost 80% of consumers expect companies to promote individual and collective well-‐being but only 28% think that companies do enough to address social and environmental issues (Havas Media 2011). Brands are now being rated on ‘meaning’ along with quality and cost. It is estimated that only 20% of brands worldwide make a “significant, positive effect on people’s well-‐being” (Havas Media 2011).

80% of consumers expect companies to promote individual and collective well-being.

Reporting on CSR progress is important to connect with those consumers looking for “specific well-‐being benefits” from a brand. The return on building a ‘Meaningful Brand’ is high; the top brands in this category outperform the market by 120% (Havas Media 2011). More than half of consumers are prepared to reward responsible companies by choosing their products and would pay a 10% price premium for a responsibly produced product (Havas Media 2011). Conducting transparent self-‐reporting allows companies to share their CSR efforts to build their reputation and brand – an important factor in the age of “immediate, open, and raw” information sharing (Trendwatching 2012). With the increased emphasis on using technology when shopping (namely ratings, reviews, and applications), having accurate CSR information available online is important to engage potential customers and build brand loyalty and trust.

The return on building a ‘Meaningful Brand’ is high; the top brands in this category outperform the market by 120%.

9. Improve Conditions via Fishery Improvement Projects

Fishery improvement projects (FIPs) are focused on improving environmental, economic, and social aspects of a specific fishery or fishing community. Organizing at the community level helps to overcome the tragedy of the commons that has a caused overfishing in the past. This typically occurs when fishers act independently in self-‐interest and deplete the shared resource because the community is not responsible for fishery management and long-‐term interests are not considered (Kinver 2013). Arnason, a professor at Iceland University, likens territorial or quantitative fishery management to being a stakeholder in a company, where there is long-‐term interest from all stakeholders to see it succeed (Kinver 2013). This can also be applied to social aspects, in which healthy and productive workers can be a benefit to the business and community.

Organizing at the community level helps to overcome the tragedy of the commons that has a caused overfishing in the past.

Organizing in this fashion can also help to address corruption, if it is a barrier to improvements within the fishery. FIPs should include a summary of the labor conditions of the fishery (such as worker safety, minimum age requirements, etc.) and address any that are deficient in their work plans. Similarly, having cooperatives with social benefits or fisheries that invest in the local communities can provide excellent communication and marketing opportunities for seafood products. Examples of these are Pacifical, the Fishing & Living™ project, and the Spiny Lobster Initiative, which speak to their social improvements work on their websites along with environmental sustainability efforts. It is important that a FIP is credible, time-‐bound, and transparent in reporting on progress against its work plan. The Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions has drafted a set of guidelines for FIPs that can be used as a reference.

It is important that a FIP is credible, time‐bound, and transparent in reporting on progress against its work plan.

10. Financial Support

Enforcement efforts in developing nations often lack sufficient funding to be successful with human rights abuses. Similarly, the development of tools to help businesses and companies assess their own supply chains for risk is often delayed because of funding constraints. Companies can reach out to NGOs and grassroots organizations working to combat human rights abuses and rehabilitate trafficked persons to learn what further support is needed. The ILO (2013) report on Child Labor in Fisheries found that prevention strategies such as education, poverty alleviation, extraction, rehabilitation, and protection for children at employable ages are important areas of focus to prevent and deter child labor in the seafood industry.

Enforcement efforts in developing nations often lack sufficient funding to be successful with human rights abuses.

Initiatives that would benefit from additional funding support include:

Financial support for illegal fishing enforcement and capacity building is also needed to combat this global issue. For suggestions of additional potential funding opportunities, please contact us.

11. Promote Positive Social Stories

The environmental movement has found that inspiring stories can help encourage consumers to alter their purchasing habits to favor more responsible products. Retailers are now starting to cater to the empowered shopper that has access to many digital resources to inform purchases and that cares about the social responsibility of products (Deloitte 2009). Companies self-report on environmental goals, and the logical next step is to do the same for social goals for seafood supply chains. As goals are achieved, that work can be promoted as a selling point for the products. Previously illustrated examples of companies promoting positive social stories are the Fishing & Living™ program and Pacifical.

The environmental movement has found that inspiring stories can help encourage consumers to alter their purchasing habits to favor more responsible products.

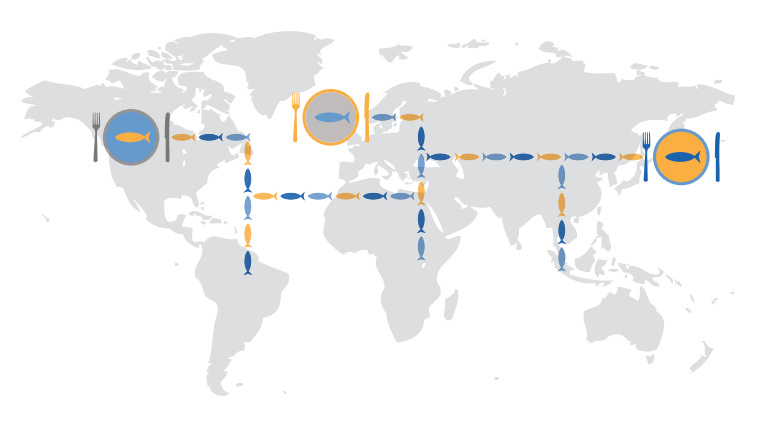

Seafood Certifications for Social Responsibility

In addition to legal mechanisms to address human rights and labor abuses in the seafood industry, market-‐based mechanisms can also be used to encourage social responsibility and shift industry norms. The power of markets in the global North to transform labor practices in regions such as the Greater Mekong Subregion and West Africa is due to the seafood industry’s supply and demand dynamic. The global North provides the majority of demand for seafood products produced and processed in the global South—in 2010, 67% of the fishery exports (gross value) of developing countries were directed to developed countries (FAO 2012; Figure 2).

According to Conroy (2001) at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, social and environmental certifications “represent creative new solutions for problems of persistent poverty by using the leverage of markets in the global North to improve the ability of workers, farmers, and other producers in the global South to build natural assets in ways that generate socially and environmentally sustainable livelihoods”.

Social and environmental certifications represent creative new solutions for problems of persistent poverty.

For the most part, certification standards in the seafood industry have been focused on improving transparency and ecological sustainability. Organizations such as the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certify responsibly managed fisheries, as well as companies sourcing from those fisheries that can verify Chain of Custody (CoC; MSC 2013).

However, the MSC certification process has no associated human rights or labor standards. In addition, many organizations that do focus on fair labor practices, such as the Fair Labor Association (FLA), do not certify fisheries production or processing operations, but instead focus on industries such as electronics, textiles, and agriculture. FishWise sought out the certification programs that incorporate social standards and are tailored specifically to the seafood industry. In addition, other certification programs focusing on worker safety, labor, and human rights that are suited for all types of industries are also listed below, as producers, processors, and distributors within the seafood supply-‐chain can easily utilize them.

The FAO, ILO, and IMO developed codes that help governments and private entities improve the social and labor standards within the fisheries and aquaculture industries.

There are also a variety of voluntary codes and standards developed by organizations such as the FAO, ILO, and IMO, which can help governments and private entities improve the social and labor standards within the fisheries and aquaculture industries. Seafood certification programs with standards incorporating human rights or fair labor requirements, as well as certification bodies were contacted and asked to provide an overview of their work.

Certification Programs

Aquaculture Stewardship Council

The Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) is a global organization working with aquaculture producers, seafood processors, retail and foodservice companies, scientists, conservation groups and the public to promote environmental and social certification and labelling program for responsibly farmed seafood. The ASC operates with Chain of Custody (CoC) certification to ensure traceability, which includes certifying environmental, social and economic aspects of the supply chain. Social and economic issues considered during the audit process include: labour rights and conditions, gender rights, cultural rights, social services, income, and value chain fairness. Launched in January 2012, the ASC set up the CoC requirements and procedures with the Marine Stewardship Council (see more details under the MSC section of this report) and uses standards developed according to ISEAL guidelines.

Fair Trade Certified Seafood

Fair Trade USA is adapting its certification process so it can be applied to fisheries in the global South. This program will focus on baseline social and environmental criteria with benchmarks for moving toward better stewardship practices, improved business capacity, and community development programs and market access, benefiting both ecosystems and people. Fair Trade USA welcomes the input, participation, and support of a variety of stakeholders in the marine sector. Fair Trade USA is actively engaging fishing communities and their processing/export partners, NGOs and experts working in the global marine sector, and funders that want to support innovative solutions for developing world fisheries. In May 2013, The Fair Trade Fisheries Advisory Council (FAC) was elected to consult on conservation, economic, and applied aspects of Fair Trade Fisheries program and Fair Trade USA is now piloting the impact potential of the Fair Trade model on fisheries in Asia.

Friend of the Sea

Friend of the Sea (FOS) is a non-‐profit organization and international certification for farmed and wild seafood. The FOS criteria are based on the FAO Guidelines for eco-‐labeling and include a social component to the audit. Audit checklists are available to download from the FOS website, for various fisheries, including inland fish farming, marine aquaculture, prawns, wild-‐catch fisheries, fishfeed and others. All the checklists include a social accountability section that has four requirements: compliance with international and ILO directives regarding child labor; remunerating workers with salaries conforming at least to the legal minimum; assuring workers’

Naturland

Based in Germany, Naturland is a 53,000 member organic farming association. The Naturland organic agriculture certification program is unique in that, unlike other organic certifications (e.g. the USDA’s National Organic), Naturland has included social responsibility into the standard with equal weight. In November 2006, the Naturland Assembly of Delegates adopted the first Standards for Sustainable Capture Fishery. The Naturland Wildfish certification standards approach ‘sustainability’ holistically and include ecological, social, and environmental dimensions. Naturland Wildfish Social Responsibility standards include: (i) respect of basic human rights as listed in UN conventions and ILO conventions and/or recommendations; (ii) freedom to accept or reject employment; (iii) freedom of association and/or access to trade unions; (iv) equal treatment and opportunities; (v) the complete absence of child labor; (vi) basic health and safety provisions; (vii) employment contracts; (iix) fair wages; (ix) payment in kind; (x) fair working hours; and (xi) basic coverage for maternity, sickness, and retirement.